After my new-fiancée (now-wife) and I got engaged, one of the things we needed to do was have each of our sets of parents visit with a priest. As I recall, this was for a character-reference “are these two suitable to be married to each other” kind of interview.

After my new-fiancée (now-wife) and I got engaged, one of the things we needed to do was have each of our sets of parents visit with a priest. As I recall, this was for a character-reference “are these two suitable to be married to each other” kind of interview.

For my fiancée, this was a routine visit; her parents were active members of their parish (and, in fact, it was their parish we were getting married in). For my mother and stepfather, this was a much less welcome visit; they had both left the Church decades earlier, gotten married, divorced, and remarried to different spouses. So, with my evidently blossoming faith, the priest may have seen a possibility to bring two lost members of the flock — my parents — back into the fold, but that was an extreme long-shot possibility.

Still, the priest did what he could to encourage them, focusing on what it would require to sanctify their (second) marriage. So he asked my mom if she was still close to her first husband (my father). She replied, “No . . . He died a number of years ago.”

The priest’s face lit up and he said, “Oh, good!” And then, realizing the implications of what he just said about my father, began stammering an apology. We smiled and took no offense — we understood the priest was thinking there wasn’t a need for any annulment if my father had passed away — but it was still an awkward, if funny, moment.

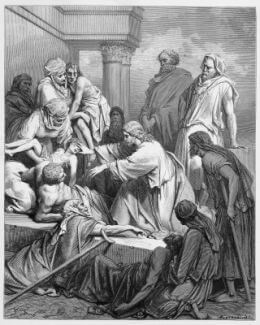

That anecdote sprang to mind when I read today’s readings. These Wednesday selections all focus on various aspects of the priesthood. The portion from Paul’s Letter to the Hebrews talks about how Melchizedek is seen as a type of Christ, representing a priesthood that is unique and eternal (c.f. footnote 7, 1-3 of the New American Bible). The Responsorial Psalm similarly speaks about this legacy, with a response of, “You are a priest for ever, in the line of Melchizedek.” And the Gospel selection from Mark looks at the story of Christ healing on the sabbath, and how this was anathema to the Pharisees — keepers of the law — who sought to have him put to death as a result.

In thinking about the priesthood, there’s an oddity about the clergy in the Church that you may not have thought about. According to the Church, the sacramental functions of the priesthood are perfect, even when performed by imperfect priests. In other words, even if you have a priest who is found to have committed terrible crimes — even actions that result in his removal from the priesthood — the rites he performs are still generally considered valid. Baptisms are not invalid even when done by a priest who is struggling with major failings. Couples married by a priest suffering from a full-on crisis of faith remain married even if the priest leaves the Church the month after. And so on. (The priest who married my wife’s parents eventually left his priestly responsibilities, ultimately marrying outside the church. My in-laws remain happily — and sacramentally – married nearly a half-century later.)

Why? Because the sacraments are actually the works of Christ, who is perfect and willing to work through the imperfections of humanity. Perhaps St. Augustine put it best: “For those whom John baptized, John baptized; those whom Judas baptized, Christ baptized. In like manner, then, they who whom a drunkard baptized, those whom a murderer baptized, those whom an adulterer baptized, if it was the baptism of Christ, were baptized by Christ.”

Think how remarkable that is! If I’m building a house, and my saw is warped, my nails are bent, my level is askew, and my hammer has a wobbly head, the resultant house will be decidedly imperfect — perhaps even unsuitable for habitation. All humans are imperfect; we have all sinned in one way or another . . . and that extends even to the priesthood. But the perfection of the sacraments shines through, though performed by imperfect people — even people who are later found as unsuitable for the job as a warped saw!

Jesus actions in today’s Gospel remind us that it is God’s will, God’s might, and God’s deeds that shine through. Christ knew that the Pharisees’ understanding of the sabbath was incomplete and inaccurate, and taught them the error of their ways by shining a light on their imperfect understanding, by doing God’s work on the sabbath. My mother and I shared a smile for the rest of her life whenever we would talk about that encounter with the priest, and his minor faux pas. Sadly, it didn’t bring her back into the faith, but I believe it helped soften tensions between us; before that, she had been bristling and mildly disapproving of her son’s Catholic faith journey. After that incident, though, I think she realized that I was still her son, and that our shared moment of that priest’s imperfection helped her understand the human aspect of the journey of faith I was undertaking.

Obviously, the vast bulk of the priesthood is made of good and honorable men. But even the most pure of priests suffers from the taint of original sin, and certainly there have been men who have struggled with issues throughout the Church’s history. Christ’s offer of forgiveness is open to all, and these errant servants can return to the fold whenever they see the error of their ways . . . but even through those tumults, the perfection of Christ is giving its miraculous gifts.

For those priests in your life, remember that they are human, just like you. They will have flaws, make mistakes, and perhaps even sin. Of course we must hold them accountable for grave misdeeds, but we should forgive them as we ask God to forgive our trespasses . . . especially for minor slips of the tongue, lapses in skill or tact, or commonplace venial failings. And marvel at the wonder that, by the Sacrament of Holy Orders, Christ is always willing and able to work through the imperfections of humanity to bring about the perfection of his great plan for the world.