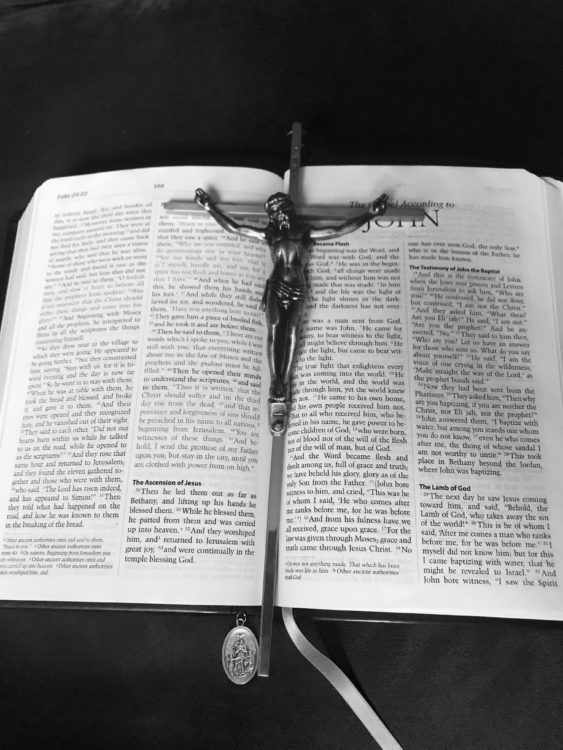

The picture today is a simple, stark cross. It is our picture today because it represents well St. Mark’s narrative of Holy Week. Of the four Gospels, Mark’s story of this week above all weeks is the shortest, the starkest, and the least favorable to the disciples. It is in many ways the most brutal. Its picture of Jesus is one of power of his fidelity, though abandoned by all.

Mark’s Gospel is the primary Sunday Gospel of Cycle B. So, today, we hear the Passion Story as Mark wrote it. Two years ago, I attended a retreat that focused on the differences in the narratives of the four Gospels by Abbot Kurt at St. Meinrad. It seems good today to share some of what I learned about Mark’s perspective.

At the retreat, we read Mark’s Gospel, then named the particular details that we noticed from the reading. As we named multiple details, Mark’s understanding of the Passion emerged with a wonderful newness and clarity. I would like to challenge you to do that. From your Bible in Mark 14:1-15:47 or as you listen in church, what catches your attention? Listen for details. Enter into the story as an eye witness in the crowd. Let yourself witness everything that Mark describes.

I would actually strongly encourage you to put this down now until after you have read or listened. Then read some of the things written here.

The Two Dinners

One was at Simon’s house in Bethany and the other was “The Last Supper” in the Upper Room. The underside of human nature is noted. The focus in Bethany is on objections to the woman’s anointing Jesus’ feet, rather than on the love in her gift. (She is not named as Jesus friend, Mary of Bethany as she is in other Gospels.)

At the Passover meal in Jerusalem, Jesus’ recorded conversation is about betrayal. No comments about unity or love, as in John’s Gospel. No washing of feet. There is no interesting dialogue between Jesus and Judas. The institution of the Eucharist is short and to the point, “Take it, this is my body,” “This is my blood of the covenant which will be shed for many.”

Mark’s Gospel describes Jesus’ Passover meal that was reminiscent of what Passover was meant to be in Exodus. “This is how you are to eat it: with your loins girt, sandals on your feet and your staff in hand, you shall eat like those who are in flight.” (Exodus 12:11) The original Passover was a very serious meal. So is Mark’s description of Jesus’ Passover meal. It IS to be the Passover of the Lord. Except this time, God Himself will experience human death. God Himself will give his life, “the blood of the covenant which will be shed for many.” Death is not imposed on sinners. Death is experienced by Jesus. The Lamb of God will be God making a new covenant with all of humanity, all of us.

And, in Mark’s Gospel, he does it alone.

Prayer and Arrest in the Garden

In the garden Jesus prays. Alone. In Mark’s Gospel there is no direct response from God as Jesus asks that he not have to offer the cup of his blood. Jesus’ resignation that it must be done is seen in the way he responds to those who come to arrest him. He says nothing to Judas. He does not support the person who cuts off the high priest’s slave’s ear. His final words before arrest are, “Let the scriptures be fulfilled.”

This is too much for the disciples and they flee—one physically naked, all spiritually stripped of the faith they thought they had.

The Trials

The narrative of the trials tells of Jesus’ trial before the Sanhedrin and Peter’s trial in the courtyard. Jesus stands firm that he is the Christ. Peter, who some months before said, “You are the Christ,” now says, “I do not know him.” Mark makes the difference stark and uses it to further develop his picture of Jesus abandoned–yet fully faithful, fully self-giving.

Then, in the narrative, there is Peter’s second trial when Jesus looks at him and the cock crows. Peter now is convicted of his failure and weeps—a bit of redeeming touch in Mark’s story. Jesus stands firm; Peter, the disciple, does not. Yet Jesus fidelity changes Peter.

In Jesus’ second trial, before Pilate, the focus shifts from religion to politics. Mark’s portrait of Pilate is stark and simple. Pilate makes no effort to convince the crowd to let him release Jesus. He gives in to them. But, this time, Jesus isn’t mocked as “Son of God” or prophet, he is mocked as “King of the Jews.” Now disciples, religious leaders, and government turn against Jesus.

Crucifixion, Death, and Burial

Mark’s only words of Jesus from the cross are “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” They are words of Psalm 22, which was prophetic of the crucifixion and, in its later verses, expressive of God’s presence and care. Yet Dr. Brown describes it this way,

“This cry should not be softened, any more than Jesus’ plea to his father in Gethsemane should be softened. It is paradoxical that the cry is quoted in Aramaic which carres the tone of intimacy of Jesus’ family language, and yet now for the first time, Jesus speaks to Yahweh as “God” instead of as “Father.” Mark is brutally realistic in showing that, while this desperate plea causes some to offer Jesus wine, it leads to skeptical mockery by others whose cynicism about Elijah’s help constitute the last human words that Jesus will hear—and no Elijah comes to deliver him.” (Brown, p 30-31.)

But the Father, Yahweh, does respond. Mark names it simple, straight: the curtain in the temple is torn in two, top to bottom. You can almost hear it rip!

There is apparently scholar discussion of the meaning of this. Is God expressing displeasure—or is God saying in effect, “the covenant with the Hebrews is now changed to include all?” Brown takes the perspective that Jesus obedience, even to death, with the blood he shed, changed everything. Now the goodness of God–and the Way of God–is open to all.

The next verses tell of an outsider, a Roman centurion, saying, “This was the son of God.” Then, a Jewish man, Joseph of Arimathea, comes forward to claim the body. Now that Jesus finished his mission ALONE, he begins to gather people to himself.

But it is not a gathering at a table of plenty. Mark’s Gospel says Jesus calls to us from the power of the cross. The cross is central to Christianity.

Again, according to Raymond Brown, this is core for accepting salvation: the reality of the cross must be accepted as reality for Jesus and reality for his followers. Joseph and the centurion represent the openness to that salvation by both Jew and Gentile. Mark adds a final detail, that Mary Magdalene and some other women watched to see where Jesus was laid to rest. This is the bridge to Mark’s story of the Resurrection. The disciples come back–albeit not the Twelve or the Seventy, but the women who had followed Jesus on the sidelines, caring for his and his disciples practical needs. Silent disciples. Yet disciples in practice. True followers.

Applications

The details here are provided to encourage you to actively engage with the texts of the events of Holy Week. May your week be blessed, set apart, deep and rich in worship and community.

Prayer before a Crucifix

Look down upon me, good and gentle Jesus

while before Your face I humbly kneel and,

with burning soul,

pray and beseech You

to fix deep in my heart lively sentiments

of faith, hope, and charity;

true contrition for my sins,

and a firm purpose of amendment.

While I contemplate,

with great love and tender pity,

Your five most precious wounds,

pondering over them within me

and calling to mind the words which David,

Your prophet, said to You, my Jesus:

“They have pierced My hands and My feet,

they have numbered all My bones.”

Amen.